The nation’s largest public housing authority, NYCHA, has for decades been plagued by a classic “pay-to-play” culture of corruption. In February 2024, authorities announced the arrest of 70 current and former employees, who were charged with extorting and misappropriating over $2 million. In return, contractors received contracts worth $13 million for work ranging from plumbing to window replacements. The Bronx was a key hub in the scheme. There, as in other boroughs, building managers and assistant supervisors demanded between 10% and 20% of the value of small repair jobs that bypassed competitive bidding. This is a look at the massive investigation and its unexpected consequences on bronx-yes.com.

A Long-Running Scheme of Small Contracts

As far back as 2019, the city started raising alarms. Suspicious patterns were found in NYCHA’s system for awarding small contracts. The same suppliers were repeatedly winning deals that allowed them to bypass competitive bidding procedures.

The scheme, ironically, began with a good idea. For years, NYCHA had accumulated hundreds of thousands of repair requests from residents. To speed up the process, local managers were allowed to award micro-contracts for sums up to $5,000 (and later up to $10,000). The goal was to simplify and expedite work: instead of lengthy tender processes, contractors could be quickly brought in for small jobs.

In reality, however, it backfired. These small contracts became a breeding ground for abuse. In nearly a hundred of the city’s over 300 housing complexes, a “percentage tariff” took root: contractors would give a portion of the payment to NYCHA employees to secure the desirable contracts. Prosecutors estimated that over ten years, the bribes amounted to more than $2 million. In exchange, a group of “friendly” companies received contracts with a total value exceeding $13 million.

Meanwhile, residents themselves waited years for repairs. As of spring 2024, open repair requests surpassed 600,000, with the average completion time ballooning to 371 days.

Audit Results

A large-scale audit conducted by the Office of City Comptroller Brad Lander only confirmed the extent of the violations.

Auditors found dozens of instances where the housing authority couldn’t prove that the paid work had ever been completed. In some cases, the amounts were shocking. For example, 19 contracts for bathtub replacements in the Bronx cost $186,000, and nearly $176,000 of that amount had no confirmation of actual repairs. A separate sample of 10 housing properties showed even more troubling statistics: of the $646,000 in micro-contracts, half had no evidence that the work was ever done.

All of this was possible due to weak or nonexistent oversight. The scheme operated for years: NYCHA employees would take a kickback of a few hundred or a few thousand dollars and push through contracts for plastering, plumbing, and painting. Comptroller Brad Lander stated the obvious: without strict controls, even small deals turn into a huge black hole where taxpayer money disappears.

The Largest Bribery Arrest in DOJ History

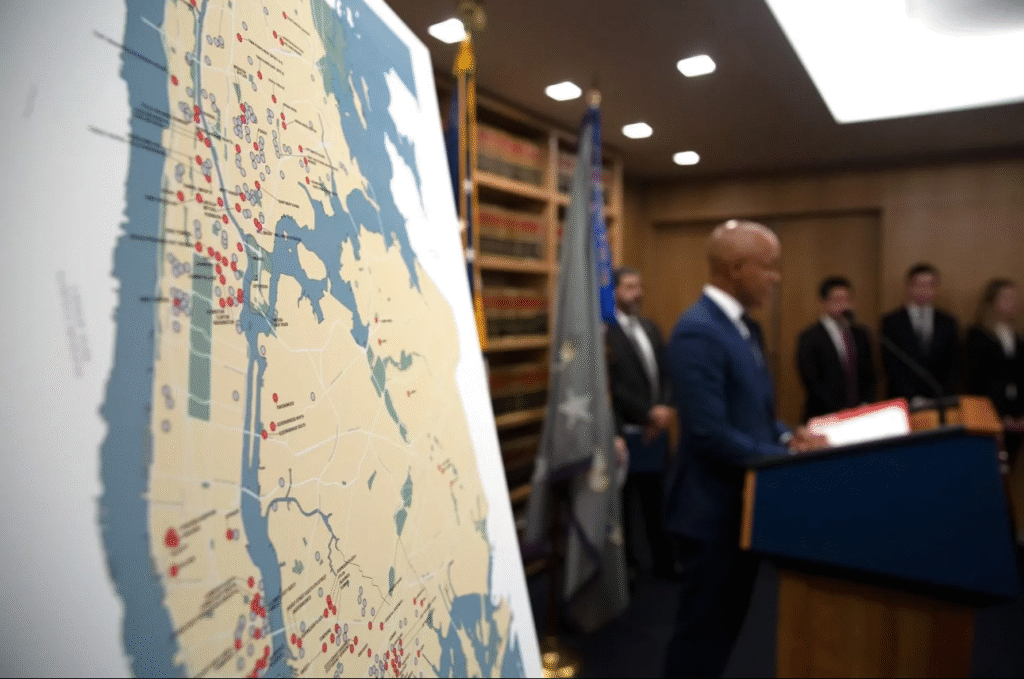

At a high-profile press conference, U.S. Attorney Damian Williams declared that corruption within the NYCHA system was so pervasive it had affected nearly a third of the city’s 335 housing complexes. That’s one in every 17 New Yorkers.

Williams called the operation the largest single-day arrest of bribery suspects in U.S. Department of Justice history. The arrests took place not only in New York but also in New Jersey, Connecticut, and North Carolina.

“Corruption has infected every corner of the city. But today, that culture at NYCHA ends,” Williams emphasized.

It’s important to note that NYCHA receives over $1.5 billion in federal funding annually. As the prosecutor stressed, residents should not have to suffer because of the corrupt games of those who are supposed to be looking out for their well-being.

The corruption scheme at the New York City Housing Authority was so extensive and long-running that even the contractors themselves lost track of how many officials they had bribed. Harjit Singh, the owner of Metro-City Renovations, when asked in court how many NYCHA employees he had bribed, responded with a bewildered look:

“Twenty to twenty-five. Maybe more, but I don’t remember the exact number.”

Since 2013, his company had received more than $29 million in contracts. He had even secured a $750,000contract for sewer repairs just five days before his arrest.

In court, Singh admitted that he had paid bribes for years to win thousands of micro-contracts without bidding. But he insisted that he wasn’t committing a crime because the money was being extorted from him.

“I didn’t know if it was legal or illegal. If I was giving somebody money for some work, that’s not a crime. The crime was them extorting me,” he said.

To avoid losing the flow of orders, Singh resorted to a trick: when NYCHA would temporarily “freeze” him due to a verification check (VNC) after reaching the annual limit of $250,000, he created an affiliated company under his wife’s name—Ultra Contracting. It received over $1 million in micro-contracts.

Another contractor, Suraj Prakash of Suraj Construction, went even further. He opened three companies under the names of relatives to bypass the VNC limitations. His business earned over $14 million in ten years. He was also accused of price gouging; for example, he billed $1,735 for rooftop ventilators that only cost $725.

Court-appointed monitor Bart Schwartz, who has been overseeing NYCHA for the last five years, called the arrests a “step in the right direction”: now, both employees and suppliers will know that their actions won’t go unpunished.

The results are already tangible: 58 out of 70 of the accused NYCHA employees have pleaded guilty.

A Paradoxical Ending to the Case

However, despite the high-profile scandal and the wave of arrests following the massive raid on February 6, 2024, it turns out that the corruption problem at NYCHA is far from over.

The paradox is that even after a series of court proceedings, NYCHA awarded hundreds of contracts worth $7.8 million to eight companies whose owners had publicly admitted to participating in the bribery scheme. Why did this happen?

- The pressure of reality: The authority had a critical need for repairs and chose to “look the other way” just to handle at least a portion of the flood of requests from residents.

- A lack of information: NYCHA officials stated that they didn’t have an official list of corrupt suppliers because law enforcement refused to provide one.

- The stance of the investigative bodies: The New York City Department of Investigation (DOI) explained that it considered the contractors not as criminals but as victims of a “pay-to-play” system. Therefore, the names of the companies were withheld.

As NYCHA spokesperson Michael Horgan said,

“Without this information, NYCHA does not have sufficient evidence to disqualify a particular vendor.”

After the large-scale investigation, the Department of Investigation (DOI) insisted that the awarding of small contracts should be taken away from building managers and placed under central office control. Two years ago, NYCHA rejected that proposal, but now they have agreed to the change.

To stop the money leak and restore trust, NYCHA has introduced a series of measures:

- Micro PQL—a pre-qualified list of vetted contractors.

- Mandatory annual staff training.

- Monthly audits of all micro-contracts.

- “Anti-corruption notifications” in its internal software.

Now, contractors will only be able to work after training and a background check.

“This tool will allow us to address the daily needs of our residents promptly while also ensuring transparency and honesty. We have a zero-tolerance policy for illegal activity. We will not allow wrongdoers to undermine our achievements. We will cooperate with law enforcement to clean up the system from abuses,” said Lisa Bova-Hiatt, NYCHA’s CEO.

Despite the announced reforms, the main problem remains. NYCHA is still working with companies that have been identified as participants in bribery schemes. This raises questions about whether the new policy can truly break the culture of corruption that has plagued the system for decades.